John Cage is perhaps the most important musical

philosopher of the twentieth century. Most of his music

was more significant for the viewpoint it expressed rather

than how well it sounded. Cage introduced randomness and

unpredictability into music, a concept that was foreign to

the aesthetic of the Western world. Most people simply

hate listening to most of what he wrote, but the fact

remains that there is hardly a composer in the world today

who was not in some way directly impacted by what he did.

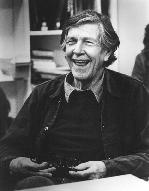

Cage is shown here with the warmest of smiles. Rather than

being a cold, isolated, ivory tower idealist, he was a

legendary nice guy, a gregarious fellow that everyone

instantly loved. I had the pleasure of meeting him myself,

the first time briefly at a party, and the second when I

phoned him to try and convince him to write a piece of

music for my newly formed rock band. However, he had other

projects going, and was not interested, but he suggested

other works of his we might consider performing. However,

I was interested in an exclusive commission, not merely in

the idea of a rock band performing something by John Cage.

As I indicated in my story, I first became aware of John

Cage when he appeared on television when I was in high

school.